Introduction

There are almost ten million menopausal women in the UK today, of whom 80 per cent will suffer from climacteric symptoms. Less than a quarter of these women, however, seek help. Unfortunately, of those who do seek medical advice, many have their questions or problems unresolved either due to lack of sympathy or poor understanding. Many women suffer in silence, too embarrassed to discus their problems. As health professionals, our knowledge of the climacteric and treatments now available should be as up to date as possible, to enable us to provide accurate and informed advice.

Indications for HRT

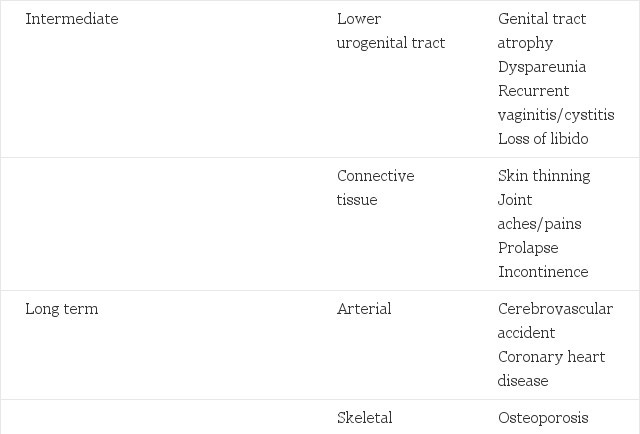

Before treatment is prescribed, it is essential to establish an indication for HRT. The main indications can be divided into three groups - acute, intermediate and long term (Table 1).

The acute symptoms occur early during the climacteric, sometimes before menstruation has ceased. Hot flushes are the hallmark of the menopause: about 70 per cent of women will experience them for two to three years, 25 per cent for five years and 5 per cent will suffer ad infinitum.

The intermediate symptoms, which usually occur after menstruation has ceased, tend to increase with time. Although many women may be reluctant to report symptoms such as vaginal dryness, it is likely that most will experience at least one problem resulting from lower genital atrophy.

The long-term effects of the menopause arise many years later and have major health implications. Up to 50 per cent of women will sustain an osteoporotic fracture during their lifetime (Lindsay and Cosman 1990).

Table 1. Acute, intermediate and long term effects of the menopause

- Premature menopause

- Caucasian or Asian origin

- Family history

- Low body weight

- Nulliparity

- Cigarette smoking

- High alcohol intake

- High caffeine intake

- Low calcium intake

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Prolonged oral steroids

- Hyperthyroid disease

Table 2. Risk factors for osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a reduction of bone density to such an extent that a fracture may occur with minimal trauma. The most common sites of osteoporotic fractures are the distal radius, vertebral bodies and proximal femur. The treatment of established osteoporosis is difficult as lost bone cannot be replaced to any significant extent. It is, therefore, important to identify those at risk (see Table 2) and initiate appropriate preventative therapy at - or soon after - the menopause. The use of bone densitometry (where available) may be of greater value in predicting an individual's risk of osteoporosis as this measures the bone density in the relevant sites.

In the UK, cardiovascular disease is the commonest cause of death in women over the age of 50 years (DoH 1994). This is thought to be partly associated with the fall in oestradiol levels after the menopause. This may lead to changes in various risk factors such as an increase in harmful lipids (Bush et al 1987) and reduced arterial blood flow (Bourne et al 1990, Vyas and Gangar 1995), although the mechanisms for this are incompletely understood.

Treatment Options

The severity of menopausal symptoms and women's interpretation of them will differ greatly and the advice and treatment given should, therefore, be tailored to fit individual needs. Careful explanation and reassurance about the forms of therapy available will aid compliance and make the client feel at ease. Treatment options may be divided into lifestyle advice, alternatives to standard HRT, and HRT itself.

Lifestyle advice

The menopause is an ideal time to give information and advice on various aspects of lifestyle, such as diet, exercise, smoking, alcohol intake and stress. Such advice may be beneficial in helping women to feel more positive about themselves and may help prevent some of the long term effects of the menopause.

Alternatives to standard HRT

There is a wide range of products available which can assist in symptom relief, such as vitamin B6, evening primrose oil and vaginal lubricating gels. Complementary therapies, such as homeopathic remedies, acupuncture, aromatherapy and yoga, may be helpful, although there are no studies to validate their effects in the menopause. In some cases, short term use of antidepressants or sleeping tablets may be useful and hot flushes may be improved by some preparations, such as Clonidine (Claydon et al 1974). Newer preparations such as Calcitonin and the bisphosphonates are of proven benefit for the treatment of established osteoporosis and may be of use in its prevention (Editorial 1990). At present, HRT is the only product available which ahs been proven to relieve symptoms (Campbell and Whitehead 1977), and reduce the risk of osteoporosis (Lindsay et al 1976, Stevenson et al 1990) and arterial disease (Ross et al 1981, Stampfer 1990).

Hormone replacement therapy

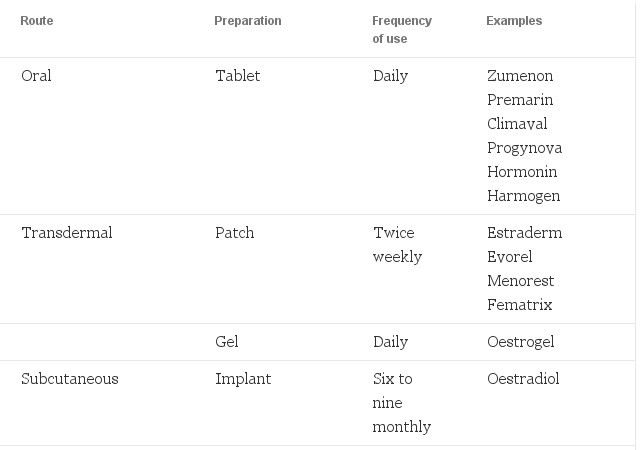

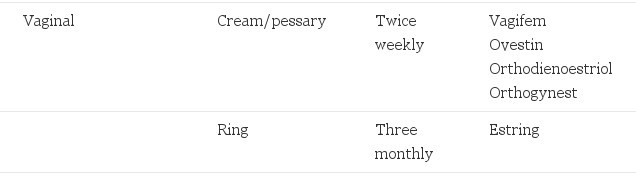

HRT consists of two hormones - oestrogen and progestogen. Oestrogen is the mainstay of therapy as it is the deficiency of oestrogen that is the cause of menopausal symptoms. There are many different types of oestrogen available which are given on a continuous basis via a variety of routes (see Table 3). The oestrogen's used in HRT are natural oestrogens. Synthetic preparations, for example, ethinyloestradiol (as used in the contraceptive pill) should not be used. In certain situations, it may be preferable to give oestrogen's via a particular route, for example, in someone who has hypertension, a non-oral route might be preferable.

But for most women without a significant medical history, the route of administration will depend more on the client's preferences and those of her clinician.

Table 3. Oestrogen preparations

Progestogens are required for women who have an intact uterus to protect the endometrium from the risk of erratic bleeding, and to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma (Sturdee et al 1978, Whitehead et al 1990a). Progestogens are prescribed for ten to fourteen days each month and until recently were only available in oral form. A transdermal form of progestogen, however, is now available, which in combination with the oestrogen patch appears to be as effective as the oral form (Whitehead et al 1990b, Hillard et al 1994). The oral forms of progestogens are listed in Table 4. A variety of combination packs are available which consist of a combined 28-day pack of oestrogen (continuous) with a progestogen (10-14 days)> These may be easier to use and thus aid compliance.

- Norethisterone: Micronor/Noriday (0.35mg-1mg)

- Medroxyprogesterone: Provera (5-10mg)

- Dydrogesterone: Duphaston (10-20mg)

- Levonorgestrel: Microval (0.075-0.15mg)

Table 4. Oral forms of progestogens and doses

No bleed treatments

The return of periods may be seen as a disadvantage by some women, particularly those some years past the menopause. There are now a number of oral preparations that avoid the problem of the withdrawal bleed, the so-called 'no bleed' preparations. These contain both continuous oestrogen and progestogen and are taken on a daily basis. They appear to be well tolerated, although a small percentage of women may get some breakthrough bleeding in the first six months (Udoff et al 1995). Tibolone (Livial) is a synthetic form of HRT which also avoids the withdrawal bleed (Rymer et al 1994). In addition, a quarterly bleed preparation of HRT is now available, in which oestrogen is given continuously and the progestogen is added for 14 days every three months, resulting in a withdrawal bleed four times a year.

Contraindications and risks

While there may be some women who will not want to take HRT, very few are unable to take HRT in some form. The contraindications for HRT can be divide into two groups: absolute and relative (see Table 5).

For those with absolute contraindications, HRT is not recommended. If symptoms are severe, however, or if there is any doubt, a referral to a specialist centre should be considered. While there are few situations in which women cannot have HRT, there are some conditions in which HRT should be prescribed with caution and these form the second group - relative contraindications.

Absolute

- Undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding

- Pregnancy

- Breast or endometrial cancer

- Severe active liver disease

- Porphyria

Relative

- Endometrial hyperplasia

- Untreated hypertension

- Otosclerosis

- Fibroids

- Diabetes

- Thrombotic episodes

- Endometriosis

- Gallstones

Table 5. Contraindications to HRT

The type and dosage of HRT used and the preliminary investigations and monitoring of therapy required may be different to that of uncomplicated cases.

If in doubt, a referral to a specialist centre should also be considered for this group. A risk is the likelihood of a condition occurring as a direct result of taking treatment. With HRT this refers to the risk of cancer, particularly the risk of endometrial and breast cancer. HRT does not appear to increase the incidence of either cervical or ovarian Carcinoma (Hunt et al 1990).

Unopposed oestrogens increase the risk of endometrial cancer. The addition of progestogens for 10 - 14 days each month eliminates this risk (Whitehead et al 1990a). It is important, however, that the dose and duration of progestogen is adequate (see Table 4) as a lower dose may not have the same effect.

One in twelve women will develop breast cancer at some stage in their lives. A large number of epidemiological studies have addressed the issue of breast cancer and HRT. Some have shown a slight increase in risk (Bergkvist et al 1989, Harris et al 1992, Colditz et al 1995) while others have not (Brinton et al 1986, Dupont and Page 1991, Stanford et al 1995). Most authorities now accept, however, that while there appears to be no increased risk with short term use of HRT (five to ten years), there may be a small increase in risk associated with longer term use (more than ten years). Certain subgroups may be at a higher risk, such as those with a family history of breast cancer at a young age or certain types of benign breast disease. It is important to remember that more women die of cardiovascular disease than breast cancer.

The ideal time to commence therapy is during the early post-menopausal years when periods have stopped completely. HRT can be prescribed earlier for distressing climacteric symptoms, but such women may be more difficult to treat as irregular bleeding may be a problem. Asymptomatic patients who require HRT for prophylaxis against osteoporosis and arterial disease should start HRT soon after the menopause. HRT started many years later will prevent further bone loss but will not put bone back, and there may still be a risk of fractures.

Vasomotor symptoms often persist for several years, so the minimum duration of therapy should be two to three years, after which treatment can be withdrawn and symptoms reassessed. Five years is the minimum duration of therapy for the prevention of osteoporosis and this will reduce the risk by about 50% (Purdie and Horsman 1990). The longer HRT is continued, the greater the reduction in risk. Epidemiological data are limited on the prevention of arterial disease, but beneficial effects have been noted within two to three years of starting HRT.

HRT should not be stopped abruptly as this can often result in an exacerbation of symptoms. The oestrogen dose should be reduced over a period of two to three months, but the progestogen should be continued for to to fourteen days each cycle until the oestrogen has been completely withdrawn. Women may experience some symptoms during the weaning-off phase and any episodes of bleeding may become scanty.

Side-effects

Side-effects can be divided into two groups (see Table 6) - those associated with oestrogen, which tend to be continuous, and those associated with progestogen, which usually occur only during the progestogen phase of the cycle. A careful and adequate explanation of possible side-effects should be given to avoid unnecessary anxiety and early discontinuation of therapy. Side-effects related to oestrogen are commonest during the first few months of therapy and usually settle. If not, they may be dose-related and either the dose or type of oestrogen used can be adjusted.

OESTROGENIC

- Breast tenderness

- Nipple sensitivity

- Leg cramps

- Vaginal discharge

PROGESTOGENIC

- Breast pain

- Fluid retention

- Bloating

- Increased appetite

- Aggression

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Irritability

Table 6. Side-effects of HRT

Side-effects related to progestogen are the cause of many of the problems associated with HRT. These are similar to premenstrual tension (PMT) and can be treated accordingly. If the symptoms persist or become severe, then the type of progestogen will need to be changed. Reducing the dose may be helpful, but the duration of progestogen should be kept at ten to fourteen days a month.

Some side-effects are related to the route of administration, for example, skin irritation with transdermal patches and nausea with oral administration. These may be relieved by simple measures such as changing the timing of taking oral therapy or moving the patch site daily. If they persist, the route of administration can be changed.

Screening and monitoring

Having established the indications for HRT, the benefits and risks should then be discussed to assist the client in making an informed decision about taking therapy. A medical/nursing history and physical examination are required and investigations such as a cervical smear or mammography should be carried out as part of well-women screening if indicated by the woman's medical history. Further investigations such as blood tests or pelvic ultrasound may be required.

The initial counselling can be carried out by the nurse or health visitor, but a doctor must perform the examination and instigate therapy. It is helpful for the nurse to see the client again after she has seen the doctor to clarify what has been said, and for any treatment regimens to be explained. The client is usually seen again after three months which gives adequate time to achieve symptom control and for any initial side-effects to settle. Specific enquiry about persistent symptoms and side-effects should be made and the bleeding pattern carefully monitored to ensure adequate endometrial protection is being achieved (Whitehead et al 1990a).

The withdrawal bleed should not be heavy or prolonged and should occur on or after the tenth day of the progestogen phase. The use of menstrual charts may make monitoring of the withdrawal bleeds easier. If bleeding irregularities occur which cannot be easily explained by missed tablets, antibiotics, or other illnesses, then a change in therapy or further investigations and referral to a doctor will be needed. Once the client is established on therapy without problems, she should be seen six monthly or yearly.

Conclusion

HRT has the potential to make a positive impact on women's health, and nurses have a vital role in educating women at an early stage about the menopause, its symptoms and the treatment options available, thus minimising the adverse effects of the menopause and maintaining health in later life.

© Amanda Hillard RGN. (1996) Nursing Standard 10, 22, 51-54.

References

- Bergkvist L et al (1989) Risks of breast cancer after estrogen and estrogen/progestogen replacement. New England Journal of Medicine. 321; 293-297.

- Bourne T et al (1990) Oestrogens, arterial status, and post-menopausal women. Lancet. 335; 1470-1471.

- Brinton LA et al (1986) Menopausal oestrogens and breast cancer risk: an expanded case control study. British Journal of Cancer. 54; 825-832.

- Bush TL et al (1987) Cardiovascular mortality and non-contraceptive use of estrogen in women. Results from the Lipid Research Clinics Program Follow Up Study. Circulation. 75; 1102-1109.

- Campbell S, Whitehead MI (1977) Oestrogen therapy and the menopausal syndrome Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology 4. London and Philadelphia PA, WB Saunders.

- Clayden JR et al (1974) Menopausal flushing: double blind trial of a non-hormonal preperation. British Medical Journal. 1; 409-412.

- Colditz GA et al (1995) The use of estrogens and progestogens and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. New England Journal of Medicine. 332; 1589-93.

- Department of Health (1994) On The State of The Public Health. London, HMSO.

- Dupont WD, Page DL (1991) Menopausal estrogen replacement therapy and breast cancer. Archives of Internal Medicine. 151; 67-72.

- Editorial (1990) New treatments for osteoporosis. Lancet. 335; 1065-1066.

- Harris RE et al (1992) Breast cancer risk: effects of estrogen replacement and body mass. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 84; 1575-1582.

- Hillard TC et al (1994) Long-term effects of transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy on postmenopausal bone loss. Osteoporosis International. 4; 341-348.

- Hunt K et al (1990) Mortality in a cohort of long-term users of hormone replacement: an update analysis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 97; 1080-1086.

- Lindsay R et al (1976) Long term prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis by oestrogen. Lancet. 1; 1038-1041.

- Lindsay R, Cosman F (1990) Epidemiology of osteoporosis. In Drife JO, Studd JWW (Eds) HRT and Osteoporosis. London, Springer-Verlag.

- Purdie DW, Horsman A (1990) Population screening and the prevention of Osteoporosis. In Drife JO, Studd JWW (Eds) HRT and Osteoporosis. London, Springer-Verlag.

- Ross RK et al (1981) Menopausal oestrogen therapy and protection from death and ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1; 858-860.

- Rymer J et al (1994) The incidence of vaginal bleeding with tibolone treatment. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 101; 53-56.

- Stampfer MJ (1990) Oestrogen replacement therapy and coronary heart disease: a quantatitive assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Previews in Medicine. 1; 47-63.

- Stanford JL et al (1995) Combined estrogen and progestogen hormone replacement therapy in relation to risk of breast cancer in middle aged women. Jama. 274; 137-142.

- Stevenson JC et al (1990) Effects of transderaml versus oral hormone replacement therapy on bone density in spine and proximal femur in postmenopausal women. Lancet. 336; 265-269.

- Sturdee DW et al (1978) Relationship between bleeding patterns, endometrial histology and ostrogen treatment in menopausal women. Lancet. 336; 265-269.

- Udoff L et al (1995) Combined continuous hormone replacement therapy: a critical review. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 86; 306-316.

- Vyas S, Gangar KF (1995) Postmenopausal oestrogens and arteries. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 102; 942-946.

- Whitehead MI et al (1990a) The role and use of progestogens. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 75; 59S-76S.

- Whitehead MI et al (1990b) Transdermal administration of oestrogen/progestogen hormone replacement therapy. Lancet. 335; 310-312.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus