Abstract

In this article Rebecca Jester and Suzanna Williams describe an action research project that led to a marked reduction in the fasting times of pre-operative orthopaedic patients.

Authors

Rebecca Jester BSc(Hons), RGN, ONC, DPSN, is a lecture practitioner, University of Birmingham and Birmingham Orthopaedic Hospital, and Suzanna Williams RGN, is a research sister, Birmingham Orthopaedic Hospital.

A period of fasting prior to anaesthesia for surgery is necessary to prevent aspiration of stomach contents which can be potentially fatal. It has, however, become custom and practice in many clinical settings to deprive patients of food and fluids for unnecessarily long periods of time.

The problem of excessive pre-operative fasting was recognised as early as 1883 when Joseph Baron Lister stated: 'While it is desirable that there should be no matter in the stomach when chloroform is administered, it will be very salutary to give a cup of beef tea about two hours previously' (Phillips 1993).

The rationale for conducting this action research project was to identify best practice for pre-operative fasting, following a review of the research-based literature, and to implement a programme for improving practice within the trust.

Literature review

There are a number of studies which demonstrate that it is safe practice for patients to receive food for up to six to eight hours prior to surgery (Chapman 1996, Hung 1992, Maltby 1993) and clear fluids, two to four hours prior to anaesthetic (Maltby 1993, Phillips 1993, Splinter 1990).

A study conducted by Splinter (1991) concluded that healthy adolescents undergoing elective surgery were able to ingest unlimited fluids up to three hours pre-operatively. This decreased thirst and did not affect gastric content. Modern dual isotope studies confirm findings that it takes several hours for solid food to empty from the stomach, but clear fluids take only two hours.

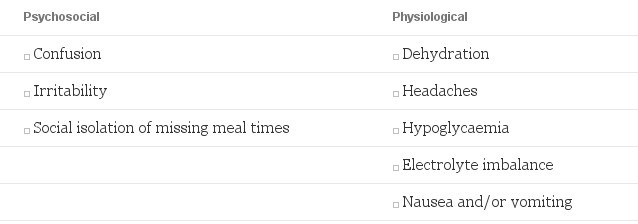

The detrimental effects of prolonged pre-operative fasting can be divided into two broad categories – psychosocial and physiological. Hamilton-Smith (1972) conducted a study assessing the opinions of anaesthetists and nurses on the management of pre-operative fasting. This study was replicated in more recent years by Hung (1992). Both studies found that, despite the knowledge of complications caused by excessive periods of pre-operative fasting, nurses and anaesthetists reported periods in excess of 12 hours for pre-operative fasting regimes. A summary of potential complications of excessive pre-operative fasting is provided in Box 1.

Box 1

Patients who undergo excessive pre-operative fasting may experience some or all of these effects, depending on their health status prior to fasting. Elderly or frail patients are particularly at risk of becoming dehydrated and confused, and this can lead to them being found unfit for anaesthesia and surgery. The question to be asked is why, when so much evidence exists, do patients still endure excessive pre-operative fasting?

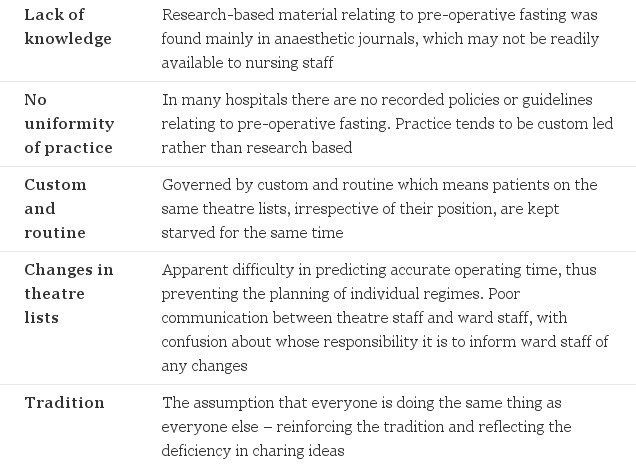

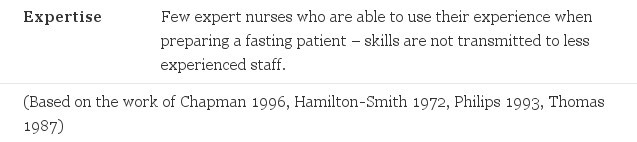

A summary of the main reasons patients endure periods of prolonged fasting is provided in Box 2.

Box 2

Following the review of the research-based literature, the aims of the study were formulated to:

- Audit existing pre-operative fasting times so that a baseline could be established to measure improvements in practice.

- Investigate potential and actual barriers to implementing research-based practice for pre-operative fasting.

- Implement a clinically based educational package for nurses to improve pre-operative fasting practice.

- Improve collaboration between anaesthetists, ward-based nurses and theatre staff.

- Re-audit pre-operative fasting times to establish if an improvement in practice had occurred following the educational package.

- Reduce the length of time patients have fluids withheld pre-operatively, minimising the potential negative effects of prolonged fasting.

Methodology and results

The methodology chosen for this study was action research that has been advocated as one of the most user-friendly and practicable research methods for nurses (MacGuire 1990). Kemmis and McTaggart (1982) developed a cyclical model of action research which the researchers used to identify current practice, establish any barriers to improving practice, implement a plan of action, and then re-evaluate to establish if an improvement in practice had taken place.

Stage 1

The problem to be studied was identified. The first stage in the action research cycle was the identification by the authors of the problem that patients were being fasted for excessively long periods prior to going to theatre. There also appeared to be some communication difficulties between theatre staff and ward staff, which meant if lists were altered, ward staff were often unaware of this. It was also found that patients on the morning lists were being fasted from midnight, regardless of their position on that list, and patients on the afternoon lists from 6am. Practice appeared to be based on custom rather than being evidence based.

Stage 2

Problem concepts were investigated and the related literature studied. A comprehensive literature review was completed and an initial study into pre-operative fasting was conducted to determine the extent of the problem. This involved the completion of a questionnaire by both ward and theatre staff, which enabled the authors to calculate the time that each patient was without fluid, prior to anaesthesia. A convenience sample of 110 elective orthopaedic patients (who had been pre-operatively assessed as fit for surgery) was selected from two adult orthopaedic wards, over a period of one calendar month. The results of this initial survey confirmed suspicions that patients were being starved for prolonged periods of time. The figures are illustrated in Figure 1. The mean fasting time was 11.94 hours which obviously far exceeds the recommended period of two to four hours, as discussed in the literature review.

Stage 3

The plan of action to solve the problem was designed. In collaboration with the senior anaesthetist, a two pronged approach was formulated to improve practice. Anaesthetists were asked to start prescribing the last possible time patients could receive food and fluid, and the authors were to implement an educational programme on pre-operative fasting in every ward and department throughout the trust. At each teaching session nurses were asked to complete a questionnaire to assess their knowledge related to evidence-based practice for pre-operative fasting.

The questionnaire asked nurses:

- If they were aware of the existence of a hospital or ward policy relating to pre-operative fasting.

- How long they thought patients should fast for.

- What research stated as safe fasting times.

- Whether they were aware of any medical conditions or drugs that delayed gastric emptying.

- If they had knowledge of the detrimental effects of prolonged fasting.

- If patients were fasted for longer than recommended by the research, why this had taken place.

To support the teaching sessions, written information packs and posters were left on each ward for reference. All nurses were encouraged to contact the authors if difficulties in implementing safe fasting times occurred. The authors also had to review the pre-admission letters that were sent to patients, rewriting the points concerning pre-operative fasting times with the approval of the consultant anaesthetist.

Stage 4

The plan was put into action and monitored. Following completion of the educational programme, the change in anaesthetists' practice, and review of the pre-admission letter, a repeat of the initial survey was undertaken to determine if any improvement in practice had occurred.

To reduce as many variables as possible, a convenience sample of 106 patients was taken from the same two clinical areas over a period of one calendar month. The questionnaire used was more comprehensive than the first one. The authors not only wanted to know if an improvement had occurred, but why it had. Additional questions included were:

- Name of anaesthetist.

- Whether or not a pre-medication was prescribed.

- Whether the last time for food and fluid was prescribed.

- Whether the patient had the last possible drink and if not, why this was.

The results of the second questionnaire show by how much the fasting times were reduced (Fig. 2).

Stage 5

A reflective stage follows where changes and modifications to the solution can be made. From the data collected at Stage 4, the following information was collated.

The mean fasting time had been reduced by 5.40 hours. Of 106 patients, 105 were seen by an anaesthetist prior to surgery. Sixty of those were prescribed a last drink by the anaesthetist. Of those 60, six patients did not receive a drink for the following reasons:

- Three patients were asleep and not woken up for a drink.

- One patient refused the drink offered.

- One patient was moved up to first on the list.

- No reason was given for one patient.

Discussion

From the findings of this project the authors recommend that to maintain and further improve pre-operative fasting, the following steps should be taken:

- Refreshers on good practice to be delivered at ward level to reaffirm the importance of patients having fluids up to four hours pre-operatively.

- Regular auditing of fasting times to be completed to ensure that the improvements gained are maintained.

- Wherever possible, the anaesthetists should prescribe the latest time for food and fluids. When this is not done, nurses should feel empowered enough to ensure patients receive fluids pre-operatively up until a safe and appropriate time.

- The collaboration between ward staff and theatre staff continues to improve so that information about changes in theatre lists can be conveyed rapidly, ensuring that patients' pre-operative fasting is appropriate.

Conclusion

This action research project has improved pre-operative fasting practice significantly, and has also enhanced collaboration between ward staff, theatre staff and anaesthetists.

The reduction in the length of time patients had fluids withheld was significant. The authors achieved the most important aim of this study which was to minimise the negative effects of prolonged and excessive fasting. The aim to implement a clinically based educational package was also achieved. It enabled the development of nursing knowledge and promoted research-based practice.

The authors hope that this study may be of help to other clinicians who intend to improve this aspect of clinical practice, although they acknowledge that this study was confined to a sample of elective orthopaedic patients, and that special considerations may need to be taken into account when preparing different types of patients for different types of surgery.

© Jester R, Williams S (1999) Pre-operative fasting: putting research into practice. Nursing Standard. 13, 39, 33-35.

References

- Chapman A (1996) Current theory and practice: a study of pre-operative fasting. Nursing Standard. 10, 18, 33-36.

- Hamilton-Smith SH (1972) Nil By Mouth? London, RCN.

- Hung P (1992) Pre-operative fasting. Nursing Times. 88, 57-60.

- Kemmis S, McTaggart R (1982) The Action Research Planner. Victoria, Deakin University Press.

- Maltby JR (1993) New guidelines for pre-operative fasting. Canadian Journal Of Anaesthesia. 40, 5, 113-117.

- MacGuire JM (1990) Putting research findings into practice: research utilization as an aspect of change. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 15, 5, 614-620.

- Philips S (1993) Pre-operative drinking does not affect gastric contents. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 70, 6-9.

- Splinter W (1991) Ingestion of clear fluids is safe for adolescents up to 3 hours before anaesthesia. British Journal Of Anaesthesia. 66, 1, 48-52.

- Splinter W (1990) Unlimited clear fluid ingestion two hours before surgery in children does not affect volume or pH of stomach contents. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 18, 4, 522-526.

- Thomas EA (1987) Pre-operative fasting - a question of routine? Nursing Times. 83, 49, 46-47.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus